The Goodness Ideal

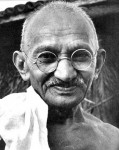

Gandhi

January 30 is yet another anniversary of the assassination of Indian pacifist leader Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869-1948). In a world marked by violence, it is always good to remember the victorious example of the Mahatma (“great soul”) who through the philosophy of non-violence achieved the independence of India.

In 1891, Gandhi graduated in Law in England and returned to India, where he was a practicing lawyer. Two years later, he started a movement in South Africa—a British colony at that time—by which he aimed to fight against racism and for the rights of Hindus.

In 1914, he returned to his country and expanded his movement, whose main method was passive resistance, and preached non-violence as a form of struggle. In 1922, he was arrested after organizing a strike against a tax increase and was sentenced to six years detention, but was released in 1924. In 1930, he led the 200-mile march to the sea, protesting against British taxation and the ban on Indians making salt. . . . Finally, the independence of India was proclaimed in 1947. Gandhi also worked to avoid clashes between Muslims and Hindus, who established a separate State, Pakistan, which was divided into two parts, one of which became Bangladesh years later. Accused of dividing the territory of India, he attracted the hatred of the Hindu nationalists. One of them shot him in the following year when Gandhi was 78. At the time, more than one million Indians attended his funeral.

Civilized civilization? Only through dialogue!

Ana Serra

In an interview I gave to Portuguese journalist Ana Serra, I stressed that Religion, Philosophy, and Politics do not rhyme with intolerance; neither does Science. Look at Voltaire’s quote (1694-1778): “Tolerance is as necessary in politics as in religion; only pride is intolerant.”

Voltaire

One more thing: one must never preach a Creator that frightens creatures, but one that makes them more responsible and fraternal.

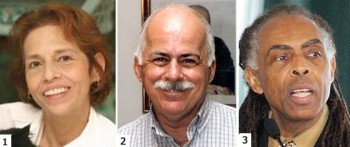

1) Sonia de Aguiar 2) Luiz Carlos Lourenço 3) Gilberto Gil

I recently read in the book, Farmácia de Pensamentos [Pharmacy of Thoughts], by Brazilian researcher Sonia de Aguiar, which was presented to me by veteran journalist, Luiz Carlos Lourenço, the following remark from the dynamic Brazilian singer and composer Gilberto Gil: “Art, religion, and science are different ways to achieve the same ends. But deep down, they are all looking for answers to the same questions.”

Goethe

These are questions that will only be elucidated when Ecumenical Fraternity becomes the foundation of religious, political, philosophical, and scientific dialogue in a civilized planetary society. Given this, the words of old Goethe (1749-1832) are appropriate here: “He who has a strong will molds the world in his own image.”

The comments do not represent the views of this site and are the sole responsibility of their authors. It denied the inclusion of inappropriate materials that violate the moral, good customs, and/or the rights of others. Learn more at Frequently asked questions.